What Does Digital Accessibility Mean?

It is a task for society as a whole to provide everyone with equal access to relevant information and digital participation. This clearly formulated guiding principle and the legal implementation deadlines in Germany since 2018 have resulted in a gradual rethinking in many different areas of life. The premise is to remove barriers. The goal is to be accessible for everyone.

To ensure that all people have access to digitally-provided information, there are many approaches and tools for making digital information processing systems accessible.

Let's take a website as an example. Everyone should be able to perceive, operate and understand it in a robust way, without any particular difficulty and, in principle, without outside help—under their individual technical conditions. Today, there is a wide range of end devices with different software, as well as assistive devices and technologies, that support people with disabilities.

Background to the Legal Situation

The legal situation can be divided into three levels: the international, the European and the national level.

International Standard: WCAG 2.1

At the international level, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1) exist as a recommendation of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). They are now established as an international standard.

European Standard and EU Directives

At the European level, various EU directives set out the principles of digital accessibility. This is based on the European standard EN 301 549, which defines the accessibility requirements for information and communication technology products and services of public authorities. Directive EU 2016/2102 applies to public authorities and defines accessible usage for websites and mobile applications. In addition, Directive EU 2018/2048 contains the associated implementation decision and a template for the accessibility declaration for the digital offerings of public authorities.

National Layer: Example Germany

At the national level, country-specific laws define individual accessibility requirements for public authorities on the basis of the international standard.

In Germany, section 2a of the Federal Disability Equality Law (Bundes-Behindertengleichstellungsgesetz, BGG) requires public authorities to design their information technology offerings to be accessible. This includes websites and also PDF documents, regardless of their size or design. In Germany, technical details are regulated by the Federal Accessible Information Technology Directive (Barrierefreie-Informationstechnik-Verordnung des Bundes, BITV 2.0). The latest version of BITV 2.0 refers to the European standard EN 301 549, which came into effect at the end of 2016 as a result of EU Directive 2016/2102 on accessible access to public sector websites.

Outlook: Digital Accessibility in the Business Sector

The European Accessibility Act (EAA) is specified in EU Directive 2019/882 and is to be implemented in national law by June 28, 2022. The aim here is to promote accessibility in online commerce. Among other things, this affects the accessible provisioning of banking and travel services, audiovisual offerings and e-books, as well as hardware such as laptops, tablets, smartphones, card readers, and parking meters.

Digital Accessibility as a Benefit for Society as a Whole

In Germany, almost 8 million people are living with a recognized severe disability. It is very challenging to statistically determine how many of these people are restricted in their digital participation. There are currently no representative figures available. A few small, qualitative surveys on individual forms of disability do exist, but these are not based on current figures.

The German Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired (Deutscher Blinden- und Sehbehindertenverband e.V., DBSV) states on its website: “Blind and visually impaired people are not counted in Germany. [...] The lack of numbers leads to the fact that in many areas responsible persons are dependent on assumptions, where they actually need planning security - as an example only the public hand is called. The DBSV demands therefore for many years empirically raised numerical material for the situation of the blind and visually impaired humans in Germany. This would be particularly important for the visually impaired sector, where the numbers of affected people seem to have been increasing dramatically for years (see WHO figures) [...]”.

Limitations can be on a visual, auditory, functional motor, or cognitive level. Examples include blindness, color vision deficiency, deafness, hearing loss, low literacy, or learning disabilities.

It's safe to say that everyone will benefit from digital accessibility at least once in their lives - temporary limitations can affect all of us. Be it tendinitis, forgotten headphones on the subway, working on a laptop on the balcony, or receiving information in a foreign language. A helpful formula could be: digital accessibility is essential for 10 percent of society, necessary for 30 percent and helpful for 100 percent.

Digital Accessibility in a Content Management System

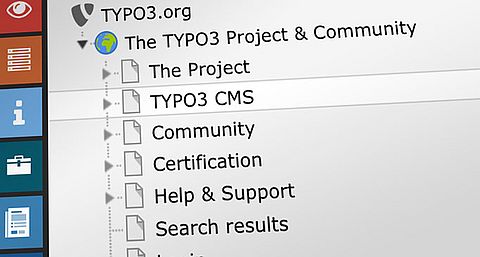

A website is filled with content via a content management system (CMS). This is usually done via the backend. In the frontend, this content is then visible to the end users of the website.

Frontend

Digital accessibility of the frontend of websites is elementarily important to ensure that the interested target group can receive the relevant information. Many technical efforts to remove barriers from websites focus primarily on accessible design of the frontend. However, the accessible design of the backend often takes a back seat.

Backend

This is precisely where universal design (an accessible design of digital living and working areas) must not stop. Professionals in this field, for example content managers, should be equally able to operate a CMS with congenital, age, environment or accident-related limitations and thus be able to do their job.

In the public sector, legislation stipulates that editors with disabilities should be given preference in job advertisements if they are equally qualified. For this purpose, the system to be used must be accessible and usable for them.

“People with disabilities still have a hard time on the job market.” As reported by the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt, Destatis) on the occasion of German Diversity Day, “nearly 57 percent of people with disabilities between the ages of 15 and 64 were employed or looking for work.”

Integrating qualified and dedicated people with or without disabilities into the digital industry and filling positions there is more successful when information processing systems are designed to be accessible.

Criteria for the Accessible Handling of a CMS

All users need textual representation of non-text elements for orientation, as well as a clearly structured and meaningful reading order, which can be experienced via the screen reader or the keyboard (tab key).

In order to enable intuitive and as accessible as possible editorial editing for all people, the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG) provide a technical reference. Authoring tools are software and applications that are used to create web content, which also includes CMSs. ATAG explains how the authoring tools themselves can be programmed and configured to be accessible and help editors to produce more accessible content.

Success criteria are formulated for this purpose. The user interface of the CMS needs to be designed in accordance with the applicable accessibility guidelines:

- Accessible (for example, alternatives for images and videos)

- Perceivable (for example, error messages or misspelled words in the editor window)

- Operable (for example, keyboard operability, sufficient time, no flashing content that could trigger seizures)

- Understandable (help to prevent errors, documentation of all user interface accessibility features, and accessible templates)

- Robust (Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies.)

Furthermore, the ATAG contains specifications for automatically generated content. Information about the accessibility of the content should be preserved or warnings should exist, for example in case of copy paste or file conversion.

The TYPO3 Backend: Is Accessible Operation Possible?

Using two case studies, we will approach the question of whether the TYPO3 backend can be used without restrictions. For this purpose, we observed two blind people in the operation of the TYPO3 backend: Matthias Henke, an editor, and Dennis Westphal, a software tester focussing on accessibility. In both cases, the operation of the backend is reduced to a few frequently used editing steps. These serve as the basis for assessing accessibility. The tests were carried out in October and November 2021 in Berlin.

Case Study 1

About Matthias

Matthias Henke suddenly went blind at the age of 15. For the past five years, he has been working as an editor at the DRK Clinics Berlin and manages, updates and edits the DRK Clinics intranet. For example, he posts news and events, updates food plans, and publishes self-produced podcasts.

Matthias Henke works with the screen reader Jaws and the 80 Braille display. There are speaker boxes on his desk. He has the Jaws license for Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and Internet Explorer 11 browsers. He works with TYPO3 v11, and uses TYPO3 v9 and v10 for the DRK clinics. The test for this article was carried out on v11.5.1.